- Home

- Tricia Wastvedt

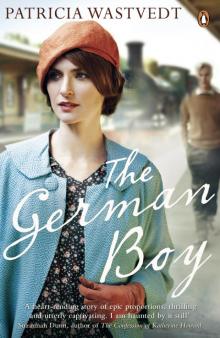

The German Boy

The German Boy Read online

By the same author

The River

The German Boy

PATRICIA WASTVEDT

VIKING

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published 2011

Copyright © Patricia Wastvedt, 2011

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book

ISBN: 978-0-67-091947-5

Contents

1947

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

1927

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

1929

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

1930

Chapter 19

1931

Chapter 20

1932

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

1933

Chapter 25

1937

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

1941

Chapter 31

1944

Chapter 32

1946

Chapter 33

1947

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Acknowledgements

For Gilly

1947

1

At just gone five, the guest in the next room went past Elisabeth’s door, his slippers flapping on the linoleum. She heard the thump of the cistern. Then the coughing horse that pulled the bread cart came and went, and soon after, the bicycle with a squeaking wheel belonging to the boy who delivered meat. Elisabeth listened to the birds singing in the rising darkness.

She had been dreaming of the garden at home in London. The sun was coming through the leaves, making patterns on the grass, and she was in her school dress collecting windfalls from underneath the pear trees. When she looked up, she saw that Karen had found a pear so big she had to hold it in her arms. It was mottled green and precious as things belonging to Karen always were. Elisabeth wanted it but Karen would only let her look. The pear wasn’t perfect after all, and instead of a bee or a slug Elisabeth saw a human baby as small as a maggot inside the flesh.

‘He’s for you,’ Karen said.

Elisabeth opened her eyes, hearing Karen’s voice as if she was alive again and standing in the room. The sunlit garden hung in the darkness for a moment.

At six, the kitchen girls arrived, giggling and whispering below the window and Mrs McCrae was shushing them and chivvying them inside. The morning light slowly illuminated the dust on the bedside table, on Elisabeth’s earrings and her wristwatch. It was almost seven o’clock.

She wondered how close the train would be. So this will happen. I will inherit Karen’s son, who I hate and love before I’ve even set eyes on him.

• • •

‘How long is it now?’ Maud asked, hopscotching by the ticket gate.

‘Soon, Maudie darling, soon,’ said Elisabeth. ‘Stay near me. Hold my hand.’ The afternoon was closing over and a porter swept up litter while a sparrow dithered round a crust his broom had missed. Other people began gathering by the barrier. ‘When is soon?’ Maud asked.

The sparrow flew up and the train came through the mist. People winced against the flying smuts and Elisabeth held down her coat, bracing herself against the swell of noise. Doors opened all along the carriages and passengers were leaning out into the light to pass down their suitcases and bags to the porters waiting on the platform. She caught sight of George way back in the crowd, but she couldn’t see anyone near him who might be Stefan.

‘I’ve seen Daddy,’ she told Maud. ‘He’s coming, Maudie.’ Maud couldn’t speak with the excitement of seeing George. Elisabeth felt it too, but even now in a crowd of faces some part of her still looked for Michael.

Don’t, for goodness sake. You won’t see him here. His life is somewhere else.

She settled her handbag on her arm, catching another glimpse of George – a middle-aged man, older than she thought her husband would ever be. He looked dazed by the long hypnotic hours of travelling and she saw him smooth his thick grey hair with the flat of his palm, adjust his hat and shoulder through a knot of people organizing their luggage. His eyes were pouched, and underneath the tan he had even in the winter his heavy handsome face was doughy as if he hadn’t slept much. Perhaps he had missed her too.

He stopped at a distance and she waved, but steam was hanging over people’s heads, curling down between them, and she lost sight of him again.

Two days ago he had gone to meet Karen’s son from the boat at Dover. The doctor at the reception shed diagnosed malnutrition and parasites, Stefan’s head was shaved, the wound to his neck was cleaned and George bought new clothes for him. The tattered Hitlerjugend uniform and rotting boots were thrown away.

George telephoned from Dover. ‘They let him through without a fuss. No one asked him anything at all – or me.’

‘Is he well, George?’ Elisabeth was sitting on the bed in the bleakest hotel room she had ever seen. The floorboards were painted brown, the Lincrusta-papered walls distempered green to match the nylon eiderdown. Above the bed was The Taj Majal at Dawn, an embroidered picture in boiled pinks hanging on a chain. She had drawn the curtains and put on the bedside lamps but the room was still cheerless. Outside the wind moaned across the hills.

She had taken the train with Christina and Maud to this hotel near York where George would bring the boy to join them. They would have some time to get to know each other before Stefan started his English education, boarding at George’s old school nearby.

She heard a muffled voice as if the mouthpiece had been covered for a moment. ‘George?’

‘I’m here. There’s someone waiting for the phone, I’ll have to go. The doctor said he’ll need time. In a few month

s he’ll be fine.’

‘Does he … does he seem …’ Elisabeth wound the telephone cord round her finger so tightly it hurt.

‘He’s just an ordinary lad, Elisabeth. Thank God they found us. I can’t believe we’re letting children suffer like this after all they’ve been through. They had no idea what was going on.’

Elisabeth’s skin prickled. Is he a child at sixteen, George? How could he not know?

‘He’s been living in a ruin somewhere,’ George went on, ‘scavenging from bins outside the Americans’ mess tents. The bloody war wasn’t the fault of boys like him any more than our children were to blame.’

She wanted to say, Our children never wore swastikas. Our children haven’t killed anyone. Instead she said, ‘We had spam fritters for supper. Banana custard for pudding, the real thing. I can’t think where Mrs McCrae got bananas. Maudie was in heaven.’

The phone line crackled. ‘Hello? Hello? George, are you still there? When will you be here, George? Maud keeps asking.’

‘We’ll be with you tomorrow. I must go. Is the hotel nice? Mrs McCrae said it’s very modern. I thought you’d like some comfort.’

‘It’s lovely, George.’

There was a pause. ‘The least we can do is give the boy a decent education. I’m going to teach him fly-fishing, and a good single malt. I’ll take him shooting. He’ll enjoy it, do you think?’

In spite of everything Elisabeth had smiled when she put down the receiver. Stefan wouldn’t need tuition with a rifle. He’d be a better shot than George.

The first passengers were coming through the ticket barrier and a man wearing a demob suit stopped dead when he handed over his ticket as if he couldn’t go on without it. He had the baffled agitated look of soldiers coming home, stranded as they were in a no-man’s-land between war and peace with no way back to either. People piled up behind him, then a girl in a swirling skirt which must have used up all her coupons for the year ran across and flung herself at him. There was a tussle between them to hold each other tight enough, to find a grip that wouldn’t fail again. The girl was laughing and the man lifted her up so her hair tumbled on his face and he kissed her hard, burying his face in her.

The dammed-up crowd of passengers divided around them, streaming out into the station, and Elisabeth turned her back on the girl’s extravagant, optimistic skirt riding up the backs of her legs. ‘Don’t stare, Maudie darling.’ She adjusted Maud’s beret which had been knocked askew by passing elbows and when she straightened up the German boy was there, smiling as if he recognized her.

‘I saw you wave,’ Stefan said so softly she could hardly hear. He gulped for air, standing close so the clamour of the station wouldn’t drown him out, and he tugged at his scarf. There were the stitches on his throat, as clumsy as the darning Maud might have done. ‘I think you must recognize me.’

‘Hello, Stefan,’ Elisabeth said. She had imagined kissing him but he seemed too tall. ‘I have a photo of you. It’s years old but you haven’t changed all that much.’ She felt silly for the lie but she was flustered, not by his height or his emaciated face and caved-in chest with the raincoat hanging like a board, but by his ease and the absence of any adolescent shyness. His blue eyes made her heart twist painfully – they were scraps of Karen given back to her and she wanted to weep because Stefan was the only one who understood it was impossible for Karen to be gone. Elisabeth fixed her eyes on the stream of passengers to keep away the tears, gripping Maud’s hand.

‘Ow,’ Maud said. ‘You’re hurting.’

Stefan wiped his bloodless lips, swallowing and swallowing. ‘Your husband pointed out places of interest on the journey,’ he said carefully. He had no accent and pronounced each word precisely like an Englishman speaking to a foreigner.

Elisabeth could feel Maud fidgeting with the worry of the introduction. ‘Say hello to Stefan, Maud.’

‘Hello,’ said Maud and withdrew into the folds of Elisabeth’s coat.

Stefan stood with his feet wide apart and swayed as if the station was rocking in a swell, leaning into the gusts of people hurrying past. He was the tiredest person Elisabeth had ever seen. ‘I’m so glad you’re here,’ she said, touching his arm.

He stared at her hand. ‘I never met him,’ he said. ‘I cannot tell you anything. Everyone asks this question. Or if they don’t, I see it in their mouths.’

‘Who?’ Elisabeth said although she knew. Stefan seemed to sag inside the raincoat as if admitting he had not seen the Führer had emptied out what was left of him. ‘It’s all right. I won’t ask you,’ she said.

At last George came through the ticket gate with a porter wheeling a battered trunk tied up with rope. Maud dashed to George and he swung her up, her mittens on their elastic and her silky hair flying. ‘My baby Mouse, I’ve missed you such a lot,’ George said and set her on the ground again. Then he leaned towards Elisabeth and she turned not quite enough so his kiss landed on her ear.

George stood swinging his arm with Maud, who had been fretting ever since he left, chirruping and dragging on his hand, and Elisabeth thought of the demobbed soldier and his girl holding each other close and not letting go. She was aware of Stefan standing quietly in the circle of her family, watching and already noticing how things were.

George smiled across at her. ‘You look well,’ he said in the way that meant he loved her and had forgotten all the ways she’d let him down. She felt the pieces of herself slipping back in place.

‘The car’s outside,’ she said. ‘Christina’s waiting. She wouldn’t come in with us.’ George didn’t comment and Elisabeth let her annoyance flare a little because nothing ever seemed to trouble him.

‘Christina is my big sister, by the way,’ Maud said to Stefan. Holding George’s hand made her bold. ‘And Alice is the other one but she’s at home in Kent.’

‘Alice,’ Stefan said. ‘I have three cousins. Christina. Maud. Alice.’

‘You see. A house full of women. I’m glad you’re here, old boy,’ said George.

Elisabeth walked on ahead, searching for the car keys in her handbag, and she tried to believe in her husband’s stubborn faith that anything works out if you want it to enough.

• • •

Christina rubbed a circle on the glass, breathed on it, rubbed again with her glove, hunching down in the back seat of Mr McCrae’s Hillman and keeping to the spot on the leather where her back had warmed away the cold.

People were coming out of the station and she looked for a daffodil smudge that would be Maud, beside a green coat and a dark grey overcoat that would be her parents. There would be another figure too. The misted windows of the car added to the blur of Christina’s short sight. She would have worn her spectacles if the German boy hadn’t been arriving.

The black afternoon gusted rain and the street lamps made a spangled chaos of reflections. She watched the shapes of passers-by, the men in raincoats, the women in threadbare make-do coats with shopping bags. Two nurses crossed the road, heads down and wrapped in capes like bats with folded wings. A soldier stopped to light a cigarette and a plume of smoke curled upwards in the sulphurous light, then he flicked the match into the gutter. He walked carefully as if he’d had too much to drink.

People were going home. Evenings ought to mean gramophones, Christina thought, girls smoking Craven ‘A’s and boys lounging on the sofa arms and being Frank Sinatra. At their hotel, evening was a time of bleakness and cutting draughts. They would all sit nearly in the hearth, scorching at the front, icicles hanging off their backs, and later Maud would creep into Christina’s bed to thaw her toes and cause torment with her snuffling. It was strange to stay somewhere less comfortable than home.

The two days they had been in Yorkshire waiting for the German cousin had stretched out, wearisome and dull. The hotel provided meals and different views of rain. Christina had dust behind her eyes from too much reading, and Maud had seethed with boredom. She asked a hundred times when Stefan would arrive.

Ye

sterday they found a stack of jigsaw puzzles in a cupboard in the sitting room. Maud made Christina put down her book and they did Africa, Dark Continent, A Busy Day in Toytown and Autumn in a Tranquil Woodland Glade until they were stupefied with twisting little wooden pieces this way, that way. The cardboard boxes smelled of old children and the fusty innards of the cupboard.

‘Will Stefan be good at jigsaws, do you think?’ Maud had asked. ‘Do Nazis like them?’

‘You can ask him tomorrow, Maudie.’

At last the waiting was over. There was a tetchy clicking on the Hillman’s windscreen as Elisabeth tapped with the keys. Maud pooched her lips against the glass. Christina unfolded herself and got out.

Elisabeth gave her a little shove. ‘This is Christina,’ she said cautiously as if this was a trick that didn’t always work.

‘Hello, Christina,’ Stefan said in a rusty-iron voice. ‘It is a pleasure.’ His smile was so nearly a sneer it teetered on the brink of good manners and he shivered hard. ‘It is a pleasure.’ Saying it a second time made it sound like a disappointment he would make the best of.

Christina said, ‘Golly, you look hungry.’

The German cousin was good-looking for someone with hardly any hair and as narrow as a straw but he didn’t look as if he minded. The dusky yellow light was hiding him, it seemed to her, and if she could catch him from a certain angle she’d see that really he was broad and strong. It was clear he was the kind of boy who didn’t care what anyone thought and she liked him in spite of his mad grim quivering and his scraping voice.

‘We should go,’ Elisabeth said, jingling the car keys. ‘Stefan must want to rest after such a long journey. We can all get to know each other over supper.’

Then why didn’t we stay at home in Kent if the journey to Yorkshire is so long? Christina thought. And why leave Alice behind if he wants to get to know us?

‘Stefan is an orphan of war,’ Elisabeth had said before she went into the station. ‘Be nice to him, Christina. He has no one and we’re his family now.’

To Christina, Stefan Landau looked like someone with no use for a family.

The German Boy

The German Boy